Is there really a link between Potch and Jack the Ripper?

- Karen Scheepers

- Aug 19, 2025

- 8 min read

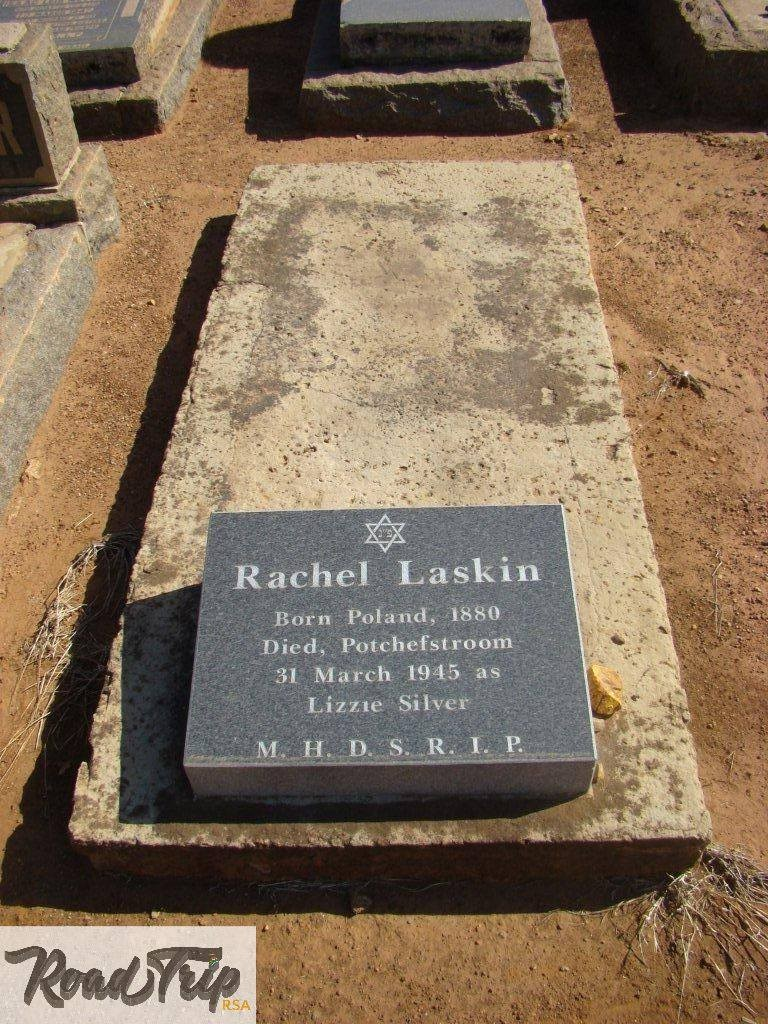

Potchefstroom’s cemeteries tell many stories, but few are as startling as the one etched onto a simple Jewish headstone: Rachel Laskin, also known as Lizzie Silver, died on 31 March 1945 after years spent in psychiatric institutions in South Africa. Rachel’s life intersected with that of Joseph Silver (born Józef Lis), a globe-trotting gangster and pimp whose violence and reach stretched from London’s East End to Johannesburg.

In 2007, South African historian Charles van Onselen argued that Silver may also have been Jack the Ripper , the unidentified killer behind the 1888 Whitechapel murders in London. This article begins with Rachel, outlines her connection to Silver, and then weighs the evidence and counter-evidence, behind the Ripper claim, asking: is there really a thread that runs from Potchefstroom to the world’s most notorious serial-murder mystery?

Rachel Laskin: a life that ended in Potchefstroom

Rachel Laskin was born to a Jewish family in Eastern Europe (sources place her in the Polish town of Opatów). As a young woman she moved to London, where she encountered Joseph Silver, by turns her handler, “husband,” and abuser. Van Onselen’s archival work uncovered records showing that Silver had Rachel committed to Valkenberg Mental Hospital in the Cape in 1901. She remained institutionalised in South Africa until her death in 1945, by which time she had been transferred to Witrand, Potchefstroom.

By the mid-20th century Witrand Psychiatric Hospital in Potchefstroom had become one of the country’s principal state psychiatric institutions (opened in 1923). Today, the hospital’s official site places it in Potchefstroom’s Deppe Street and lists hundreds of beds for long-term psychiatric care, the kind of setting where a patient like Rachel could have spent her final years.

Multiple historical accounts note that Rachel died in 1945 in a mental hospital in Potchefstroom. A Polish-language academic write-up of van Onselen’s work states plainly that “in 1945 … ‘Lizzie Silver,’ the ‘wife’ of Józef Lis … died in a mental hospital in the small town of Potchefstroom.” A South African review likewise introduces van Onselen’s book with Rachel’s “desperate story,” emphasising that she died insane and incarcerated, friendless, far from the land of her birth.

As for her grave, researchers who followed van Onselen’s leads report that Rachel is buried in the Jewish section of a Potchefstroom cemetery, an austere, local resting place for a woman whose life had been uprooted by violence. (Potchefstroom’s Alexander Park/Old Cemetery has a long Jewish section, though the site’s formal “closure” in 1905 means later burials were limited; the exact plot details for Rachel are not publicly catalogued.)

The Silver connection: coercion, exploitation, and abandonment

Joseph Silver (Józef Lis) was a Polish-born criminal who drifted into London’s East End in the mid-1880s and built a career on pimping, trafficking, brothel-keeping and violence. He used many aliases, married multiple women (often the same women he had coerced into prostitution), and cultivated corrupt relationships with police. Historical summaries, based chiefly on van Onselen’s 25-year research project, describe Silver’s marriages in London to Hannah Opticer, Hannah Vygenbaum (Annie Alford), and Rachel Laskin (Lizzie Silver), all of them fellow Polish Jews.

Silver’s modus operandi was cruelty. Reviews of van Onselen’s book, and the book itself , portray him as a sadistic exploiter of women who used beatings, rape, and terror to control prostitutes in Johannesburg and beyond. He operated brothels on multiple continents, served prison terms, and finally died in 1918 after being executed as a spy in Austrian Galicia during World War I.

In this personal story, Rachel suffered most. After years in Silver’s orbit, she was committed to Valkenberg in 1901 and later ended up at Witrand in Potchefstroom. Silver abandoned her; she died long after he had left South Africa.

Potchefstroom’s place in the story

The Potchefstroom link exists because Rachel’s last years were spent at Witrand Psychiatric Hospital, and her grave lies in a Jewish section of a Potchefstroom cemetery. Witrand today remains a large provincial mental health facility; the official site lists almost 800 usable beds and underlines its long-term psychiatric care role, a continuity with the institution’s historical function.

Local heritage resources describe Potchefstroom’s Alexander Park/Old Cemetery and its historic sections, though the formal record of all mid-20th-century Jewish burials remains incomplete online. What is clear from scholarship around van Onselen’s work is that Potchefstroom is the end-point of Rachel’s story, and the city’s cemetery forms the tangible link between a local gravesite and a global, grim criminal history.

Enter the historian: Charles van Onselen and The Fox and the Flies

The claim that Joseph Silver might have been Jack the Ripper comes from Charles van Onselen, a distinguished South African historian (Rhodes, Wits, Oxford; University of Pretoria) whose work often illuminates the underworld of southern Africa and the Atlantic world. He spent nearly three decades piecing together Silver’s movements across Europe, the Americas and Africa, culminating in 2007 with The Fox and the Flies: The World of Joseph Silver, Racketeer and Psychopath.

Contemporary coverage emphasised both van Onselen’s meticulous archival spadework and the book’s controversial final chapter, which advances the Ripper hypothesis. Reviewers from mainstream outlets noted the sensational nature of the claim but also the depth of research; academic reviewers praised the transnational reconstruction while warning of speculation in the Ripper conclusion.

Why some think Silver could be Jack the Ripper

Van Onselen and later commentators offer circumstantial reasons to consider Silver a candidate:

Time and place. Silver lived in London’s East End circa 1885–1889, learning the trade of vice amid Whitechapel’s poverty, precisely when and where the Ripper murders occurred (Aug–Nov 1888).

Victim profile & misogyny. Silver’s lifelong record shows brutal misogyny toward prostitutes, aligning with the Ripper’s chosen targets.

Psychological triggers. Accounts suggest Silver contracted syphilis in the late 1880s/1890s, leaving visible facial pockmarks; some Ripper theories posit venereal disease as a possible rage catalyst. (This is suggestive, not probative.)

Aliases and invisibility. Silver’s habitual use of aliases could explain why he never appeared under his own name in Scotland Yard’s suspect lists.

A life pattern that “fits.” Forensic psychiatrist Robert M. Kaplan (who has written about van Onselen’s work for years) argues Silver/Lis “must now be considered a serious candidate,” while conceding the case cannot be proven.

Van Onselen himself has been careful in public interviews: he calls his reconstruction “intelligent speculation,” not a solved case; but he insists the density of coincidences (place, period, persona, methods) makes Silver too strong a candidate to ignore.

Why most specialists remain unconvinced

Ripperologists and historians have pushed back on the Silver theory, chiefly because no direct evidence places Silver at the murder scenes or ties him to the canonical five killings.

Lack of contemporary suspicion. Silver does not appear in contemporary police files as a named suspect; other men (e.g., Aaron Kosminski) were regarded by some investigators as stronger leads at the time.

Age and descriptions. Witness estimates often placed the killer in his late 20s to 30s; Silver was ~20 in 1888. Eyewitness descriptions are unreliable, but this mismatch gives skeptics pause. (This point is frequently raised in reviews of van Onselen’s book.)

Evidentiary standards. Academic reviews praise the book’s research but criticise leaps from context to conclusion, noting that circumstantial patterning cannot substitute for hard forensic links.

A note on the Kosminski DNA headlines

You may have seen headlines claiming the case is solved via DNA on a Victorian shawl, naming Aaron Kosminski as the killer. It is important to understand why this is not accepted as definitive:

The 2019 paper in the Journal of Forensic Sciences tested mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from stains on a shawl said to have been found near victim Catherine Eddowes. mtDNA can exclude people but cannot uniquely identify one person, since many unrelated individuals share the same maternal-line profile.

Multiple geneticists and archaeological DNA experts called the study methodologically weak and criticised both the provenance of the shawl (no solid chain of custody; not listed in 1888 police inventories) and the lack of transparent data.

The controversy went so far that Innsbruck Medical University scientists publicly criticised the paper and the journal issued an expression of concern. In short: the Kosminski DNA claim remains contested, and the Ripper’s identity is not confirmed.

This matters for Rachel’s story because it highlights how uncertain the Ripper question remains, which, in turn, affects how we read the Silver hypothesis that grew out of van Onselen’s research.

Pulling the threads together: Potchefstroom → Rachel → Silver → Whitechapel

Putting it all in order:

Rachel Laskin, a Jewish woman coerced into Silver’s world, was committed to Valkenberg (1901), then lived out her final years in Potchefstroom, dying in 1945 and buried in the city’s Jewish cemetery. That sequence is well-attested in van Onselen’s findings and subsequent commentary.

Joseph Silver, Rachel’s abuser and sometime “husband,” is a historically documented international pimp and gangster whose career took him through London’s East End in the 1880s, the place and time of the Ripper murders, before he resurfaced in New York, Johannesburg and elsewhere, dying by execution in 1918.

The Ripper link is hypothetical: van Onselen’s synthesis of timeline, geography, psychology, and behaviour creates a plausibility case that Silver could have been Jack the Ripper. But no conclusive proof exists, and the broader research community remains divided.

So is there really a link between Potch and Jack the Ripper?

There is a documented link between Potchefstroom and the cast of people orbiting the Ripper debate, through the life and grave of Rachel Laskin. There is also a credible historical link from Rachel to Joseph Silver. The final step, from Silver to Jack the Ripper, is an informed, vigorously debated hypothesis, not a settled fact.

Why Rachel’s story should lead the telling

Even when the Ripper speculation steals the headlines, Rachel must remain the focus of the Potchefstroom story. Her life illuminates the hidden human cost behind crime histories: the women coerced, trafficked and discarded by men like Silver. Reviews of van Onselen’s book deliberately foreground Rachel’s “desperate story,” reminding us that the victims’ lives matter as much as the mystery. In that sense, Potchefstroom’s connection to the Ripper saga is less about the killer’s identity and more about memorialising a woman whose fate was sealed by his world.

Further reading and research notes

Primary synthesis: The Fox and the Flies (2007) by Charles van Onselen, the foundational biography of Silver (and the source of the Ripper hypothesis).

About the author: Van Onselen is a senior South African historian (University of Pretoria), decorated for rigorous, archival scholarship.

Assessments & critiques: Reviews from Kirkus, Mail & Guardian, and scholarly journals highlight both the breadth of research and the speculative nature of the Ripper claim.

On Kosminski DNA claims: See Smithsonian’s balanced explainer and critiques collated by Forbes; note Wikipedia’s summary pointing to a formal expression of concern by the journal.

Final Thought

Potchefstroom’s link to Jack the Ripper runs through the life and death of Rachel Laskin. Her years in South African institutions and her burial in a local Jewish cemetery anchor a story that otherwise spans continents and a century of myth-making. Her abuser, Joseph Silver, is indisputably one of the most violent figures to emerge from the late-Victorian underworld and he may have been the Whitechapel murderer. But “may” is the operative word. The best historical case we have (van Onselen’s) remains circumstantial, and rival “solutions” such as the Kosminski DNA claim remain contested.

What is certain, and what Potchefstroom can meaningfully claim, is that Rachel’s story is real, local, and worth telling with dignity. Her grave reminds us that the Ripper saga is not only a puzzle about a killer’s identity; it is also a ledger of lives broken by a transnational economy of vice and violence.

If there is a link between Potch and Jack the Ripper, it is the link of memory and warning: a call to remember Rachel, to scrutinise the men who profited from women’s suffering, and to keep separating evidence from speculation as we revisit one of history’s most haunting crimes.

Comments